Industries

Industries

How the Japan Education Sector Can Boost Your International…

By Priyanka Rana

In this article, we delve into the Japan education sector, looking at the cultural and business trends, key companies, and what future opportunities exist in Japan’s EdTech market and within the most lucrative areas of education.

Overview: Japan Education System

Japanese people consider learning to be one of life’s fundamental excellencies. That truth has driven instruction to play a vital part in their culture, particularly since the Meiji Restoration in 1868. This emphasis on the esteem of instruction has contributed to Japan’s victory in the world of cutting edge solutions.

The Japan education sector has one of the world’s most compelling success stories. The country ranks consistently among the world’s top-performing systems in the Programme for International Student Assessment, the leading international competency test among 15-year-old school students. The test is held in high regard due to the quality of learning outcomes, equity in the distribution of learning opportunities and overall value for money.

Investment in the Japan Education Sector

Less money is spent in the Japan education sector than in any other developed country. 3.3% of Japan’s GDP is invested in education, compared to the OECD average of 4.9%. Japan spends $8,748 per student at elementary school level, compared to the $10,959 in the United States, meaning Japan spends its money wisely. As textbooks are simple and printed in paperback format, students and teachers are responsible for keeping schools clean. Teachers in Japan are paid more than the OECD average, but the profession has high barriers to entry, like Japan’s notoriously difficult entrance exams, which are administered by higher authorities.

The Japan education sector has a 6-3-3-4 learning style – compulsory education runs for nine years, with six years in elementary education and another three years in lower secondary school. But more than 97% of children aged 16-18 attend senior high schools and approximately 50% of students who have completed senior high school education attend universities.

There are 3.3 million senior high school students (aged 16-18) and 3.6 million junior high school students (aged 13-15). The majority of children attend municipal schools but there are also a number of private schools. Due to the shrinking population of children across Japan, more than 200 schools have closed in recent years.

According to a survey conducted by Japan’s Ministry of Education, it was found that in fiscal 2019 there was a year-on-year decrease of 154 elementary schools and 48 junior high schools, of which there are now 19,738 and 10,222 respectively. There was a significant drop of 59,322 elementary school students to 6,368,545, while the number of junior high school students fell by 33,555 to 3,218,115.

The national government’s initial budget for education and science expenditure was set at around ¥5.38 trillion JPY ($49.8 billion USD) in 2019, almost the same amount as the initial budget of the previous year, before being retrospectively revised. The education budget is one of the largest within the national government’s general account and more broadly focuses on the promotion of culture, education and science in Japan.

Adoption of English Language in the Japan Education Sector

In the early 1600s, thanks to initial contact between Japan and Europe, almost all students graduating from high school in Japan had several years of English Language Education under their belt. Japanese students experience great difficulty in studying English, due to fundamental differences in grammar and syntax, as well as important differences in pronunciation. In the 1990s, many people opposed teaching English in elementary school as they thought it would confuse children who hadn’t even learned their mother tongue yet.

In 2002, the Ministry of Education introduced English classes as an optional subject in elementary schools. Then, in April 2011, English language instruction became compulsory starting from the 5th grade of elementary school (students aged 10-12). The main purpose was to ease the transition from primary to junior high school, where English has long been compulsory, and to expose young children to other cultures. The long-term aim was to improve the lowly position of the Japan education sector in terms of international English proficiency standings: Despite these efforts, Japan ranked fifth from the bottom in the 2015 TOEFL Examination. According to a survey conducted by the Ministry of Education in fiscal 2015, only 4.9% of elementary school teachers were licensed to teach English.

In 2019, Japan dropped to 53rd in global proficiency, squarely placing the country in the “low proficiency” band. Today, Japanese are caught between a belief in the importance of Japanese language and culture and the need to exist in a globalised world in which English carries economic privileges and status. For years, multinational corporations have been using English as the common corporate language.

In April 2020, English became a mandatory subject for fifth- and sixth- graders, instead of a foreign language activity class where children are only expected to experiment with English by speaking and listening. This doubled the annual number of English classroom hours to 70 from 35, and saw reading and writing taught for the first time. With this change, foreign language activity classes also became mandatory for third – and fourth – graders.

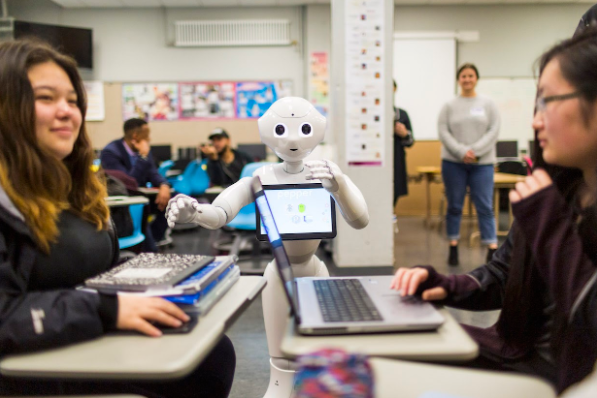

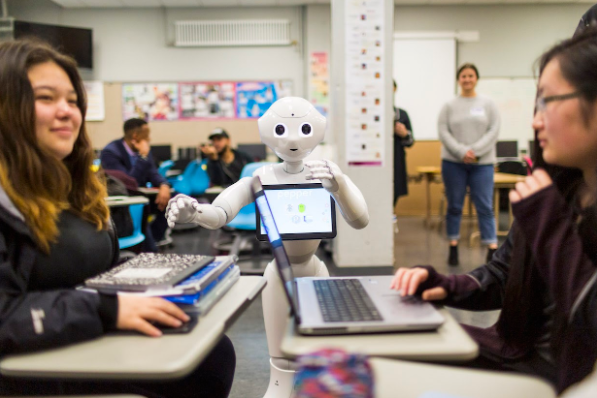

The Role of Robotics In the Japan Education Sector

The use of robots is rapidly becoming more common across educational institutions, workplaces, and homes, many schools have started teaching robotics. These robots can help deliver lessons in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) concepts that are an essential part of the curriculum. Robots can also be useful for children that are home-schooled or for teaching in areas where human experts are in short supply. The Ministry of Education invested ¥250m JPY ($2.3m USD) to roll out robots across 500 classrooms to help teach English. In countries like South Korea, a robot called Robosem has been adopted to teach English.

The Education Board in Hiroshima prefecture has pioneered the use of a pint-sized “surrogate robot”, measuring just 23-centimeters in height. OriHime by OryLaboratory is placed in a classroom to act as an avatar for an ill student in hospital. This Orihime robot simultaneously records and broadcasts content and students can watch on their tablets.

Nao, the 25-inch robot designed by Softbank, was found to increase preschool kids’ spontaneous learning: the unplanned and unstructured eureka moments that can widen a child’s worldview. It helps young students study English vocabulary, serve as classroom dunces and for those who commonly make mistakes. It is synonymous with a younger brother or sister and this human model robot was not developed to play the role of human teacher or caregiver. Instead, this robot is a “care-receiving robot”.

Minnie, who is 13 ½ inches tall, programmed by Michaelis, is a companion robot that listens and makes occasional thoughtful comments to individual children who read books. The comments that Minnie makes about books demonstrate some understanding of what is happening in the story but that understanding is not presented in an authoritative way. It makes eye contact with the child, averts its gaze when speaking and moves subtly in idle moments to appear more lifelike and relatable.

What the Japan Education Market Needs to Progress

Numerous companies operating in Japan’s education system offer technological services for English learning as Japanese people are now aware that communicating effectively is crucial for global interaction. Many companies are releasing robots that are able to teach STEM subjects, and maker spaces are spreading quickly, especially among private schools. Japan is also known as “The land of video games” and to this effect, the Japan education sector is adopting many gamification tools like Gamelearn, as well as VR and AR devices, which are predicted to be part of the “new normal” due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

Elementary school students discuss self-driving cars in Social Studies and use sensors to identify issues based on experience and hard-science data. In music education, students are taught through Yamaha’s Vocaloid, and also with robots such as Makeblock’s Codey Rocky. There is a big demand among parents for building-block kits for their kids and programming courses for themselves. Now special training on related tech topics is being offered at some cram schools, or juku.

What do edTech and education companies need to focus on for the Japan education sector?

Japan has earned a reputation for exporting successful products and services from different industries. In technology, Sony and Nintendo are among the most internationally recognized brands. In education, the tutoring centre Kumon has franchises across the world.

But when it comes to the education technology industry, few people outside the country can name Japanese companies off the top of their heads. And for Norihisa Wada, an education investor who treeks the globe in search of promising EdTech startups, that lack of exposure is one of the biggest challenges currently facing Japan’s education technology industry.

Bridging Japanese companies to education technology investors and markets across the globe is one of the goals for EduLab Capital Partners, an investment fund where Wada is a general partner. Launched this March, the Boston-based firm traces its roots to a Japanese educational research and assessment company, JIEM. EduLab has already invested in seven EdTech startups and is a limited partner in three U.S.- based education-focused venture capital firms: Fresco Capital, GSV Acceleration and LearnLaunch.

We’ll be adding more articles on Japan’s education sector in the future, so keep checking back or follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook or Twitter to get notified about our latest posts!

Alternatively, get in touch to find out how we can help you promote your educational tool or service in Japan.