Culture

Culture

Zen, Shinrin-yoku, Ikigai? The Exoticisation of Japanese Buzzwords

By Ryoko Ward

Zen, shinrin-yoku, ikigai— you may have heard of these words. Although each one is used differently, what’s common is the fact that they are all Japanese terms that have become widely accepted in the west. They also all share an underlying ‘spiritual’ or ‘mindful’ sentiment. In their original Japanese context, however, they don’t necessarily signify spirituality, at least not to the same extent as they’ve come to do in the west.

Zen: a form of Buddhism the Japanese don’t really talk about

The word zen gained popularity in the west more than five years ago, at least in business scenes, including Google who invited Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh to seek mindfulness, sustainability and happiness in their workplace. Zen has been widely used in the consumer market in the west as well — for example, the OnePlus 7 Pro smartphone has an inbuilt ‘Zen Mode’, which enables users to turn off notifications in twenty minute chunks, and they’re not allowed to cancel the session except to make emergency calls.

The term has also been applied to other industries such as F&B (i.e. ‘Zen Metro’, a restaurant in Birmingham), Health (i.e. ‘Micro Zen’, a supplement by Biocyte) and Design/Architecture (i.e. the ‘Zen inspired’ residence by DP Architects).

This tells us that, at least in the west, the word zen has wide ranging meanings — from ‘spiritual’ and ‘mindfulness’, to ‘relaxing’ and ‘healthy’, ‘quiet’ or even at a more fundamental level, ‘Asian’.

So what exactly does zen mean to Japanese people?

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the primary definition given for zen is: ‘relaxed and not worrying about things that you cannot change’, followed by ‘a form of Buddhism, originally developed in Japan.’ The Cambridge Dictionary is not wrong, but technically the definitions shouldn’t be listed in that order if we’re referring to a general perspective. Among Japanese people, only the latter definition is considered to be correct, and it’s quite unlikely that they would associate the word with the first meaning, which is closer to how it’s commonly used in the west.

In fact, the word zen is rarely used as an adjective or verb in Japan. Examples of this might include; ‘(to) get zen’, ‘(to) zen out’ and ‘(to) feel zen’. In this way, the word zen can be used in casual day-to-day conversations in a western context. But in Japan, on the other hand, the word simply isn’t heard as frequently. Because zen carries the sole definition of being a form of Buddhism, unless they’re specifically making reference to the religion itself, it’s simply rare to hear Japanese people using it at all.

The fact that Japanese people tend to shy away from talking about religion helps the situation, particularly when it comes to one’s personal beliefs. Overall, Japanese people consider themselves to be rather secular. Declaring oneself to be religious (not only Buddhist) is perceived as a rarity and can even be deemed as being dogmatic and strange to others. It’s also considered inappropriate to talk about religious beliefs in business situations.

For this reason, the fact that zen has now taken on so many meanings and has become so deeply integrated into the western consumer market might come across as rather bizarre to Japanese people.

Shinrin-yoku: nothing more than a ‘walk in nature’

It can be said that shinrin-yoku is almost like an update of the zen phenomenon in that it has a similar usage within a western context.

Shinrin-yoku can literally be translated as ‘forest bathing’, but it shouldn’t be taken to mean anything other than ‘walking in the woods to relax’, at least from a Japanese perspective. A Guardian article notes that, ‘Forest bathing has become a national pastime in Japan. It can reduce stress and even heal our bodies — maybe it’s time us Brits tried it as well’, and encourages the readers to ‘turn off your phone, and make the most of your five senses’.

It’s easy to imagine Japanese people taking selfies while engaging in shinrin-yoku, uploading photos to their social media accounts while walking in the woods, and still claiming that it falls under the definition of shinrin-yoku. The point is that in a Japanese context, the word shinrin-yoku doesn’t hold the same special meaning as it does in the west. Therefore, it really might be too much to exclaim that ‘it’s time us Brits tried it as well’; saying that seems to suggest that it never existed in Britain prior to the word gaining popularity. But this isn’t strictly true.

Because shinrin-yoku only has a basic, surface level meaning among Japanese consumers, products such as the Shinrin-yoku Candle by Earl of East (below), which describes shinrin-yoku as ‘a Japanese ritual that involves taking in the forest atmosphere’ is likely to come across as especially comical to Japanese people, for whom shinrin-yoku is not a ritual unique to their culture, but refers simply to the act of walking in the woods to relax.

In fact, some online articles and videos in Japanese have discussed the western trend of focusing on shinrin-yoku, stating how they’re often surprised by the fact that the concept is perceived as being so unique to a non-Japanese audience.

Not that Japanese people are necessarily aware of this fact, but shinrin-yoku was first coined by the former Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Tomohide Akiyama as recently as 1982. So considering that the term only has thirty-seven years of history, associating it with the ‘traditional’ culture of Japan in the same light as Shinto or Buddhism is rather odd to begin with. In a book about shinrin-yoku by Oliver Luke Deloire, he notes that, ‘the ancient Japanese philosophy of shinrin-yoku’ is definitely based on the ‘western’ interpretation.

The way in which shinrin-yoku is over-spiritualised in the west compared to how it’s used in Japan is one example of how concepts from one culture can be exoticised in another to give brands a unique and competitive edge.

Ikigai literally means ‘life purpose’, but it’s not necessarily an outrageously huge idea

For Japanese people, the word ikigai means ‘life purpose’ or one’s ‘raison d’etre’. It does imply something spiritual on a personal level, but the expression is also used casually to mean ‘things that make you feel happy in your everyday life’. While the word certainly originates in Japan, it doesn’t mean every single Japanese person can claim to have their own ikigai. If asked what their ikigai is, most Japanese people are likely to be taken by surprise and say, ‘that’s a big question’. Not many would be able to give an answer right away.

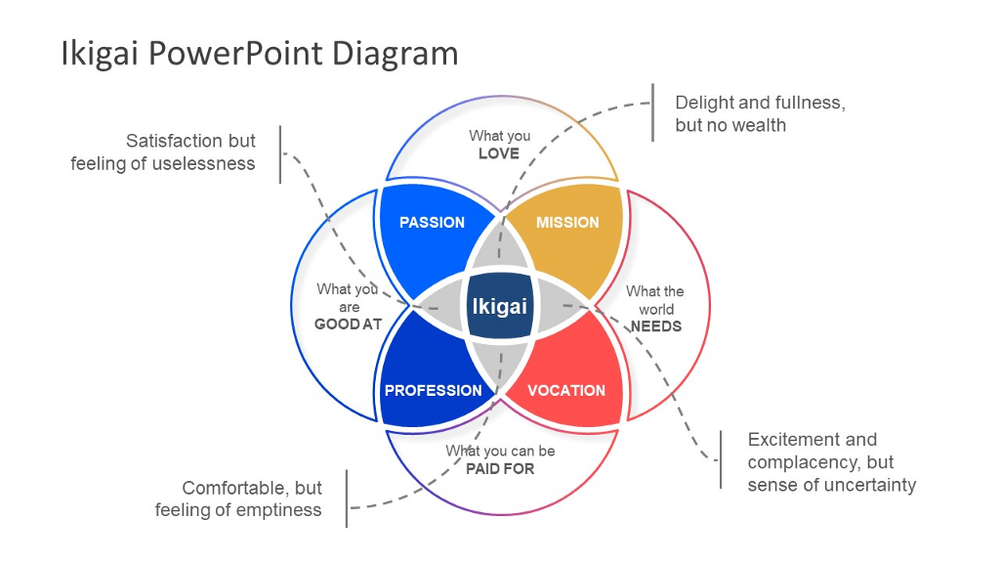

What’s different about the western definition of ikigai is that the word is loaded with various overlapping concepts, which are often illustrated in a diagram such as this one:

It’s safe to say that almost no Japanese person would be able to explain the term in such a structured way. This kind of diagram is definitely not the first thing Japanese people would tend to think of when they hear the word ikigai.

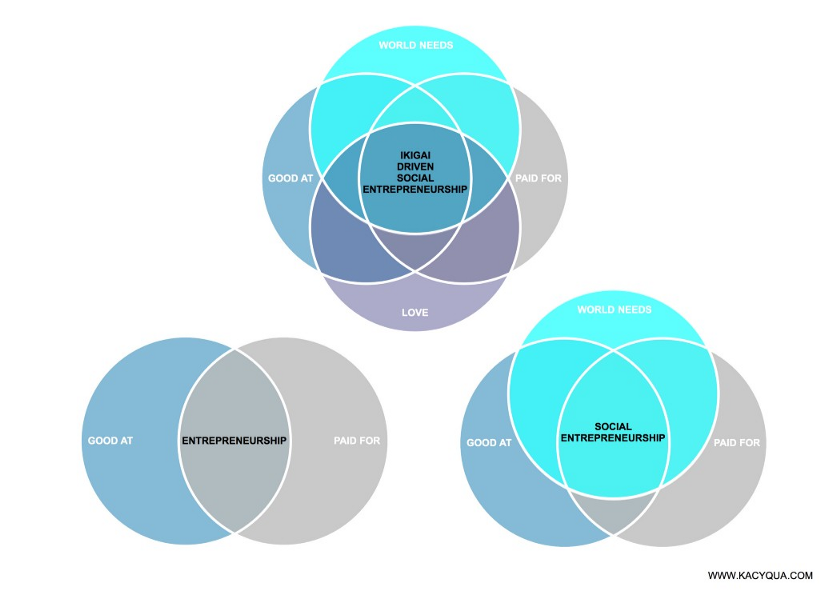

The philosophy of ikigai is now commonly applied within western business settings, particularly with regards to entrepreneurship and management. Again, by making use of a diagram, an article like this explains how the concept can help people uncover key areas of focus in business planning to ensure they succeed.

Again, this is not the typical way Japanese people would consider the word ikigai. It tends to be implemented at a more personal level. Applying the concept to business thinking in such a systematic and scientific way would not be top-of-mind for the majority.

Ikigai as a re-imported Japanese buzzword

Despite the different meanings, Japanese people don’t necessarily dismiss the way certain words have been ‘exoticised’ in the west. In fact, in some cases, Japanese buzzwords are actually re-imported into the Japanese vernacular, complete with the exoticised, extended meanings attributed to them in the west.

Ikigai is a solid example of this. Although still not deemed the most common usage of the word, the popular ikigai venn diagrams are now often translated and incorporated into Japanese social media and blog posts as guides instructing people how to live their lives to the fullest.

What can Western brands learn from this?

Skewing the meanings of trendy foreign terminology for western audiences can be an effective tactic for boosting appeal and tastefully ‘exoticising’ a product or service. The lesson when addressing the Japanese market, however, is not to be misled by what you think is inherently ‘Japanese’ in nature when crafting brand messages. Certain aspects of Japanese culture that are widely known and accepted in the west are not necessarily perceived the same way.

If brand representatives misunderstand the original definition within the local context, it’s easy to veer off message and they’ll most likely end up having little impact or even be seen as comical.

Got a question about a buzzword? Get in touch with us here.