Insights

Insights

Japanese Pop – The growth of the Japanese music…

By Roma Patel

The Japanese music industry is not only one of the biggest music markets in the world, but a cultural phenomenon too which has resonated with people within and outside of the borders of Japan, especially since the 2000s which saw a stark rise in the popularity of Asian music worldwide.

Jpop, or Japanese pop, is a musical genre which first started to emerge around the 1950s. Following World War II, American influences, particularly rock and roll, impacted the pop culture scene in Japan, allowing it to begin taking its own shape. The 80s and 90s saw a significant turning point for Japanese pop, in which artists such as Seiko Matsuda and Hikaru Utada quickly became household names. Jpop is now a genre crowded with pop groups, boy bands and girl groups in which there are “idols”, and although the genre is labelled as “pop”, this does not mean it is limited to a single genre of music.

Japanese pop is far from a monolith, it is a diverse landscape in which groups can explore genres such as jazz, rock and electronic music, and the popularity of the music has been accelerated by platforms such as Twitter and TikTok, in which the music can now be spread by listeners, allowing Japanese idols and groups to gain traction, which has had a massive impact on the Japanese music market.

In this article we break down how the Japanese music industry has developed over the past decades, not only musically, but also in regards to the culture it has created with its audience.

The roots of Japanese pop

Japanese pop music began to rise within the 1950s and 60s, with Western rock and roll influences being incorporated into the existing traditional enka (Japanese music genre), before the popularisation of the kayōkyoku (literally meaning “pop-tune”) style of music. The 1960s saw Japan face massive economic expansion in the wake of World War II, with the annual growth rate being around 10 percent, even reaching 13 percent, compared to the 7.2 percent it had been in the year before its introduction.

This was a result of the income doubling plan which was implemented as a method of reaching and maintaining a high economic growth rate, which is exactly what it did. Following this era came the rise of folk music in Japan, which were linked to more Western styles and had typically universal messages. This popular era of folk music saw the emergence of singer-songwriter Yosui Inoue, which was followed by an era of “New Music” in Japanese pop, which introduced many new bands to the music scene.

The next years saw a rise in the “city pop” style of music, which became a staple genre in the Japanese music industry within the 80s, merging the funk, R&B, jazz fusion of its sound with retro urban aesthetics which evoked a sense of escapism, matching the aura created by the music. Numerous singers and icons of this era involved themselves in the aesthetics of city pop, centering their fashion around this concept, thus influencing their audience to do the same.

The 1980s began to see the rise of female “idol” singers (idols refer to people working in pop culture, typically in the music industry), who were pushed to uphold a clean image. This was an extremely important quality to have in order to maintain a fan following, much like it is in the present, and this emergence of idol singers continued to rise through the 1990s, which saw the genre of Jpop enter mainstream music and become the standard within the Japanese music industry.

Groups such as Mr. Children and B’z rose to popularity through their more band-oriented sound, shortly followed by singers who focused on making more dance-oriented music, such as Namie Amuro. Others, such as Ryuichi Sakamoto, chose to venture into various genres of music, basing their sound on what was most trendy at the time and collaborating with other artists.

The popularity of boy bands and girl groups continued to surge throughout the 90s and into the 2000s, where the Japanese music industry saw an influx of idol groups, along with developments in technology which made it easier for Jpop to be reached by a global audience.

Japan’s music industry: Overview

The Japanese music market is a significant economic powerhouse, being the 2nd largest in the world, after the US. In 2022 alone, Japan’s music industry saw sales of 307 billion Japanese yen (USD$2.4 billion) through recorded and digital music. Its growth has been driven by a number of factors; one of them being the enduring popularity of the Jpop industry, with devoted fans showing their support for their favourite artists by purchasing albums both physically and digitally.

The years following the pandemic have also seen an increased interest and demand for live performances and merchandise from music artists, which has impacted the Japanese music market greatly.

The fan culture of purchasing CDs, merchandise and concert tickets is prominent within the younger generations, where the allure of meet-and-greet opportunities and exclusive content causes devoted supporters to purchase more albums, bolstering the dominance of physical media sales in this market. Moreover, consumer preference for physical CDs can be partly due to Japan’s ageing population, with 29% of the population being over the age of 65 years.

Japanese idol and fan culture

A pivotal part of Japan’s music industry has been the emergence of Jpop idols and their fans, which has impacted not only the Japanese music industry, but the worldwide music market since the start of the 21st century.

The idol industry is centred around music companies recruiting teenagers and young adults and training them to be singers, dancers and rappers. The recruitment process, pioneered by Johnny Kitagawa (founder of Johnny & Associates), was then adopted by many other companies as a method of manufacturing Japanese idols.

This process was later used by music companies in the Korean music industry, as a method of creating K-pop idols. Within these groups, individuals are often given specific roles, for example being the “main dancer”, “lead singer” or the “visual”. They can then be marketed around these characteristics by releasing content for the fans which focuses on these roles.

Although different companies may have different rules for idols to follow, the rule on privacy remains mutual across most companies – idols’ private lives must remain private in order to maintain their aforementioned “clean” image, with idols facing restrictions on doing anything that may cause a scandal, such as being seen with a significant other, or smoking. Being caught in a scandal can often result in many fans boycotting the artist or company, or the idol may even be suspended.

The most prominent scandal that has emerged in the past year involves the pioneer Johnny Kitagawa himself; hundreds of victims voicing that they faced sexual abuse from the late music mogul. Having fostered the most famous boy groups in the country, this news created shockwaves in the Japanese music industry, with various Japanese idols coming forward and sharing their stories of abuse that they faced whilst working under his company.

This movement somewhat mirrored the #MeToo movement in the West – which was not welcomed as much in Japan partially due to the country’s gender equality climate. This is not to say it had no place however – many women did get involved, and related trends such as “ku-too” were born, fighting against the strict and arguably sexist nature of some workplace dress codes.

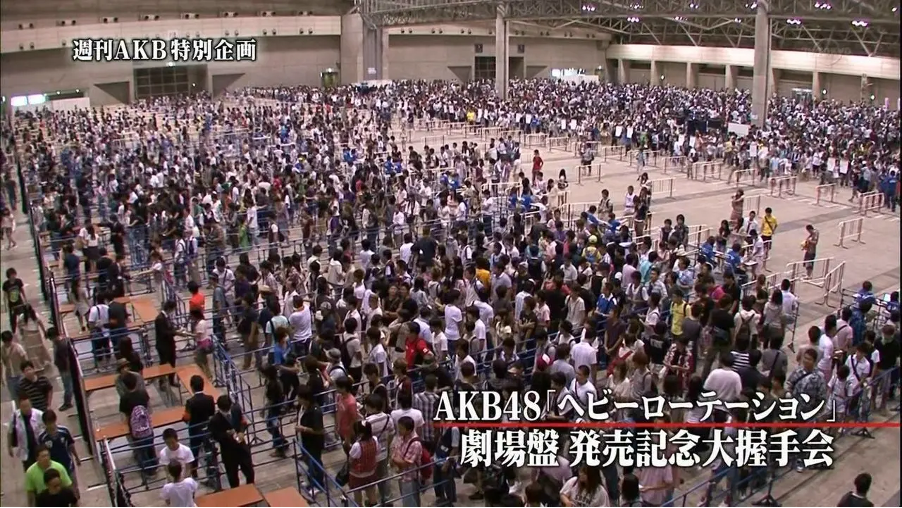

Once an idol makes their debut, they begin to appear on music shows (such as Music Station, Love Music and CDTV) in which they can perform their new releases, television shows and hold in-person events as a means of promotion. A popular event in the Japanese music industry for idol groups specifically, is handshake events, in which fans can meet their idols and shake their hand in exchange for buying their albums. The more albums they buy, the more entries they get.

This has had a great impact on the Japanese music market, as devoted fans will tend to buy as many albums as they can in order to get a chance of meeting their idols – and with albums in Japan generally being priced at around $25, such events can become extremely profitable for the music companies.

Idol groups such as AKB48 and Arashi, who debuted at the beginning of the 21st century continue to top the charts in Japan, proving the success and impact of the idol industry on the Japanese music market.

In order for albums to appear high on the Japanese Oricon Charts, they must have a high number of sales, both physically and digitally, and streams. However, there is a limitation to this method of charting. Sales that are shipped outside of Japan are not counted towards the charts, as a result of previous instances of foreign fans mass-purchasing albums in order to see their favourite artists chart.

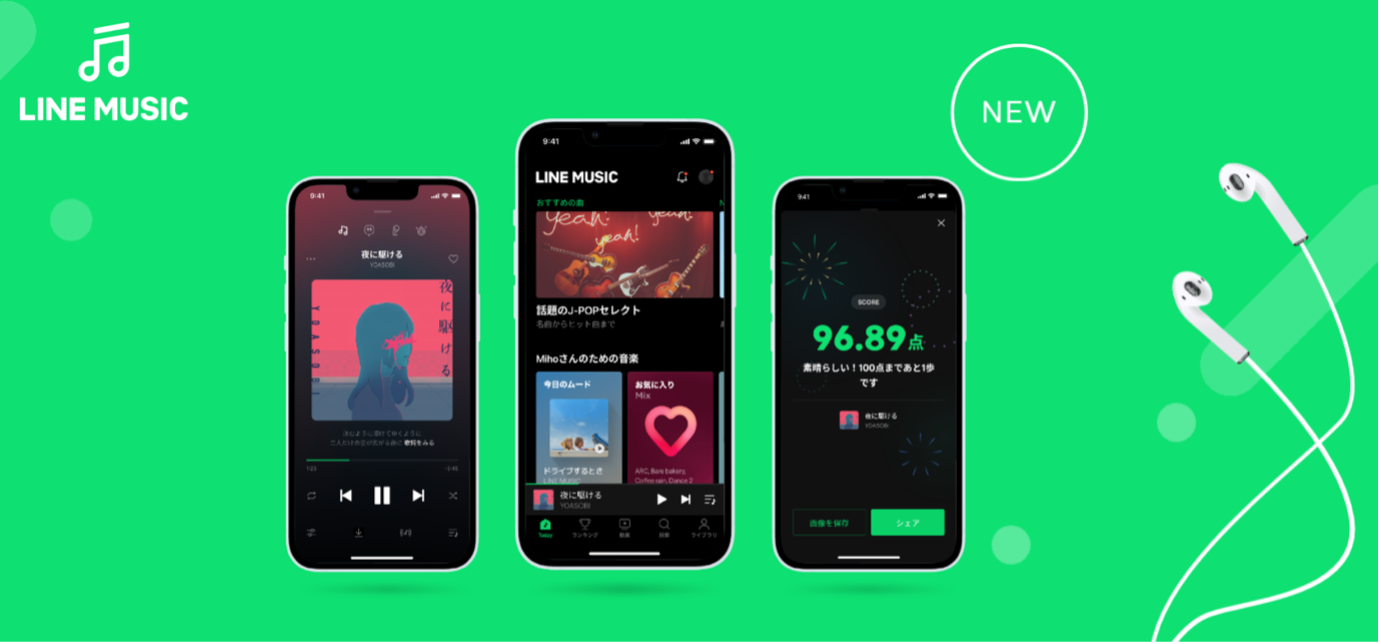

The introduction of streams counting towards the charts was a more recent development, having been implemented in 2018. The songs can be streamed on services such as Line Music, Rakuten Music and AWA, which will then contribute to the song’s chart placement.

Are the Korean and Japanese music industry similar?

Japan’s neighbouring country, South Korea, saw a growth in their own music industry, with K-pop idol groups facing a similar recruitment process, working under a management and releasing various contents as a means of promoting their new music.

Appearances on Korean music shows (such as Music Bank, Inkigayo and The Show) allow for artists to perform their music but unlike with the Japanese shows, the artists have the chance to win a trophy at the end of the show depending on how many votes they have received for their new song. A large number of music show wins generally indicates an artist’s domestic popularity, as fans are required to stream and vote on Korean services such as Genie and Melon.

Streaming on such services, along with Spotify for international listeners, has now become one of the most important aspects of the Korean music industry, along with buying the albums. Album sales, digital sales and streams land the songs on the Gaon and Hanteo charts (the equivalent of the Japanese Oricon chart) and their positioning is a determination of their popularity. This knowledge, paired with the numerous events that require the buying of albums as an entry, means that hundreds of thousands of albums, sometimes even millions, are sold within the first few days on release.

One of the significant differences between the Japanese music industry and the Korean music industry is their targeted audience. Whereas Korean music companies are usually focused on garnering worldwide attention for their artists, Japanese music companies are much more focused on building and maintaining the domestic fanbases of their groups, due to the size of the market within its own borders. In 2022, around 88% of physical album sales in Japan were domestic, with only 12% being international, mirroring the figures on the digital side.

As a method of attracting the attention of the Japanese audience, Korean idol groups tend to release Japanese versions of their singles and full albums which they then promote in Japan. This is uncommon for artists in the Japanese music industry, as an artist’s popularity tends not to be measured by their global success.

In some instances, Korean idols collaborate with popular Japanese idols, which can attract the attention of the Japanese general public if the artist is exceptionally famous. For example, the collaboration of Suga of BTS – the most popular group in the Korean music industry – and Ryuichi Sakamoto – one of the most distinguished composers in the Japanese music industry – which garnered over 33 million streams on Spotify alone and debuted at number 3 on the Oricon chart.

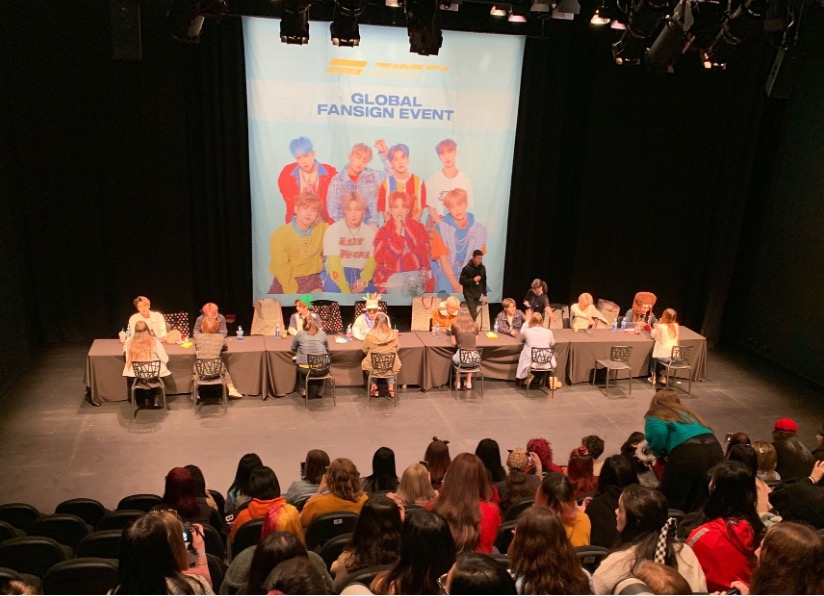

Much like Japanese handshake events, fansigns are important promotional events for Korean artists, where fans can have their album signed by the artist (through the same entry system) and have a face-to-face conversation with them, with these events frequently occurring internationally now.

The pandemic saw a pause of in-person events and the emergence of online fansigns (where fans can video call with their favourite artists) and online live-streamed concerts (live-streamed on platforms such as YouTube, and also on domestic Japanese sites for live-streaming concerts such as Mahocast (which acts as a virtual venue) and Eplus, which released a streaming platform alongside its main business as a ticket sales and distribution platform.

While Japan-only events do exist, this helped open up Japanese live concerts to fans all over the world. With the fansigns following the same entry system, these have had a significant impact on the Korean music industry and charting system, with some fans buying hundreds of albums to win a 3 minute call with their favourite artists.

Japanese music – streaming or buying?

The U.S music industry saw the great success of streaming platforms, such as Spotify and Apple Music in the 2010s, which soon became pillars of the music industry, accounting for over 80% of music revenues in 2022.

However, the Japanese music industry has not adopted the trend of relying on streams for the majority of music revenue. Due to the fan culture of purchasing physical albums and the age demographic of Japan, 2022 saw physical sales accounting for 66% of music revenue, contributing 129.8 billion yen to Japan’s economy, and digitals accounting for 34% – still on an upward trend in the Japanese music industry. The pandemic pushed the industry to focus more on digital platforms, with streaming accounting for 88.4% of Japanese digital music revenue in 2022.

CDs can be purchased in stores such as Tower Records and HMV, which sometimes offer exclusive pre-order benefits for certain albums in their stock – such as new photos or vouchers for priority concert ticket purchasing. However, specialised stores such as Disc Union are where the vinyl records can be found, which are still widely popular. 2021 saw vinyl production and value increase by 70% in comparison to the previous year, as a result of foreigners mass-buying records due to the easing of COVID-19 restrictions across Japan’s borders.

Shops such as Mercari and Amazon Japan have CDs available to purchase online, with Amazon Japan even offering international shipping in some cases. Japanese music can be streamed on sites such as Line Music, Rakuten Music and AWA, in which, according to a survey conducted in Japan in December 2020, 53% of respondents were between the ages of 12 and 19 years. The survey showed that the lowest streams were coming from users in their 50s and 60s.

Although the transition to digital streaming has been gradual, there has been significant growth, with streaming revenues increasing by 25% in 2022. While traditional music consumption methods remain prevalent, the emergence of these new trends in the Japanese music market indicates a growing appetite for digital platforms that offer accessibility and personalised music experiences.

The global reach of Japanese music

Despite the immense success of the Japanese music industry within the country’s borders, the artists face a limited global potential, with their companies disregarding international promotion, which can be disappointing for some fans. However, due to the colossal size of the country’s music market, Japanese music companies often overlook this and focus on catering to their domestic fanbase.

Furthermore, the impact of Japanese music and Jpop can be seen globally, not only through the support of the fans, but within fashion and aesthetics – which are fundamental components of the industry. The styles of popular Japanese idols are often mimicked by supporters, or are used as inspiration for Western aesthetics, thus bringing further attention to the industry.

Final words

The great success of idol and fan culture within the Japanese music industry continues to bring in billions of Japanese yen, making it difficult for non-Japanese artists to gain a strong position in the Japanese charts. With the country having developed its own system of creating popular artists, businesses looking to expand into the Japanese music market must consider the differences in the market landscape.

From differing consumer tastes and popular distribution styles/platforms to other local cultural phenomena, it may be necessary to localise your approach in order to gain success. This is the case across the board when expanding between cultures. The success of foreign companies in the Japanese streaming market is a great example of how localised business strategy and marketing techniques can help foreign businesses hit the ground running.

Although streaming has taken over Western music markets, physical sales remain the biggest generator for sales in the Japanese music market, which is something that foreign businesses looking to expand in the Japanese music market should consider. However, as the popularity of digital music streaming in Japan grows, so does the accessibility of the music and domestic music companies are beginning to recognise the opportunities that streaming can provide.

Are you looking to learn more about or enter the Japanese music market? Contact us for a 30 minute first consultation at no cost to discuss how we can help you reach your goals.

See also: The Japanese Streaming Market: The Rise of SVOD Platforms and the Importance of Localization

Keep checking back or follow us on LinkedIn or Twitter to get notified about our latest posts. We’ll be adding more articles on seasonal and cultural occasions in Japan, so watch this space!

Alternatively, feel free to get in touch and see how we can help you develop your offering in the Japanese market.