Consumer Insights

Consumer Insights

How localising the #MeToo movement spawned The #KuToo movement…

By Ryoko Ward and Melissa Francis

Although to a lesser extent compared to the west, Japan is one of the countries where the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment took place. Given the unique Japanese social context, some alternative movements gained traction in light of this, namely #WeToo and #KuToo. Focusing on these examples, in this post Tokyoesque discusses the ways in which global movements can be localised in Japan to maximise impact.

Why did the #MeToo discourse not resonate as much in Japan?

After the #MeToo movement had become visibly active in the west, people in Japan also started to use the hashtag to join the global movement and tackle their own social issues in the process. However, whilst the movement didn’t grow as much in Japan as it had done in the west.

Shiori Ito, a freelance journalist from Japan who is now based in London, explains this in her interview. Based on her own experience as a rape survivor, she thinks the reason why the #MeToo movement did not take off in Japan to the same degree is partly due to the specific Japanese social context, where there is a significant stigma around speaking up about individual experiences. Backlash against speaking out and instances of victim blaming are also prominent, which means many people try to avoid conflict to begin with.

Bringing the #WeToo conversation to the forefront

Along with other members, Ito went on to found a platform called ‘#WeToo Japan’, reflecting the idea that speaking up as a collective (‘we’) is more comfortable than doing so as an individual (‘me’). The #WeToo websitesees representatives from Japanese companies putting their names forward to declare their working environments as being free from harassment.

Organisations like Voice Up Japan are fighting to raise the stakes for improved gender equality in Japan, which is still largely a patriarchal society. This article from Savvy Tokyo, raises a key point — the word gaman (endurance) is often seen as being equivalent to a law or virtue among Japanese people. Even today, there is a tendency to remain silent in the face of adversity and pretend it never happened. This is seen as preferable as opposed to confronting the issue and voicing an alternative opinion. This underlying notion of needing to demonstrate gaman applies mainly to women and they can often be criticised or dismissed by others when voicing ‘socially unacceptable’ views.

#Kutoo is another social movement in Japan that stemmed from the #MeToo movement. As The Guardian explained in their article, #KuToo is a pun on the words kutsuu (苦痛), which means ‘pain’ or ‘suffering’, and kutsu (靴), meaning ‘shoes’. Using this hashtag, gravure idol and writer Yumi Ishikawa started an online petition asking the government to ban companies from forcing women to wear high-heeled shoes at their workplace. The petition gathered more than 16,000 signatures and it was submitted to the government only to find that, unfortunately, Labour Minister Takumi Nemoto refuted the idea of banning heels saying, ‘It is socially accepted as something that falls within the realm of being occupationally necessary and appropriate’.

The fact that the #KuToo movement has garnered so much support from women across Japan reflects the significant level of demand for the liberty to wear more comfortable shoes at work.

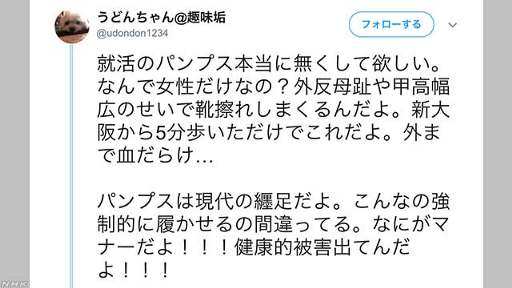

The tweet below was retweeted the most (at least 6000 times).

I really wish I did not have to wear heels for job hunting. Why do only women have to be forced to wear them? Because of hallux valgus and the shape of my feet, I get a lot of sores from my shoes. My feet are covered with blood even after a 5-minute walk from Shin-Osaka station. Heels are almost like a form of modern foot binding. It is so wrong to force people to wear these. What part of this is etiquette? It is causing real health problems!!

NHK did an interview with the person who tweeted this and she said, “I went to an internship programme in flat shoes such as sneakers and loafers, but I was told they were inappropriate. This made me think that not wearing heels might be a disadvantage when I’m job hunting so I forced myself to wear heels regardless. My feet bleed and hurt so much but I have to wear them everyday, which is really hard for me. I thought this is such an unjust idea and felt angry, which is why I tweeted this.”

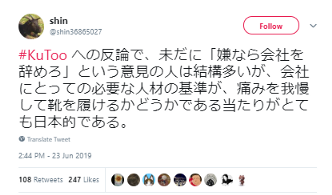

In response to #KuToo, there are many people who still have the opinion ‘if you don’t like it, just quit your job’, but whether or not you can bear with the pain is a very Japanese standard in terms of HR practices.

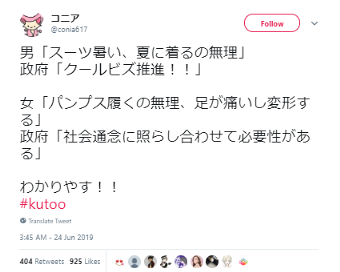

Men: ‘Suits are too hot, it’s impossible to wear them in the summer.’

The Government: ‘COOL BIZ Campaign!!’

Women: ‘It’s impossible to wear heels, they hurt my feet and deform them.’

The Government: ‘It’s a social norm, so it’s necessary.’

The tweet above compares government initiatives skewed towards favouring male workers, but mocks the ignorant response to women’s complaints concerning high heels.

The ‘COOL BIZ’ campaign the tweeter mentions was started in 2005 and sees offices setting their air conditioning units to a certain temperature, both as a means of saving electricity and keeping people cool. It is not limited to male employees but certainly takes into consideration the heaviness of suits during the humid weather.

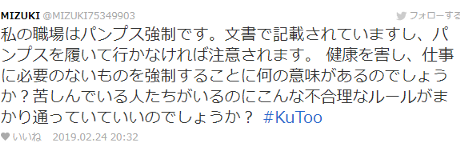

My workplace enforces the high heels rule. If you don’t wear them, you will be cautioned. What is the meaning of unnecessarily harming health at work? Is it really okay if these kinds of rules pass when there are people who are suffering?

What can brands learn from the localisation of these movements?

One of the key takeaways from the #WeToo example is that a collective, group-based approach to social issues is often advisable, especially where bold, against-the-grain statements are being asserted. A concept focused on individual rights might seem like a very empowering thing in the west, but in Japan it’s more effective to show an individual’s relationships with others, and coming together to fight for a common cause.

The #KuToo example also demonstrates that puns can be extremely powerful when it comes to building traction around an idea. Wordplay is a mainstay of Japanese culture, and while it is normally attributed to comedy skits, the #KuToo movement proves that wordplay also has its serious uses in Japan as well as for branding purposes. Consider ways you could boost appeal around the product or service you’re trying to promote by using well thought-out linguistic and visual cues that will resonate with local consumers.