Interviews

Interviews

Interview with Akio Fujii, Japan M&A Specialist

Japan M&A transactions have been on the rise. Since 2014, the number of outbound M&A (Merger & Acquisition) transactions from Japan increased by 58% to reach a total of 720 deals in 2019 with Asahi Group’s acquisition of Australian drinks giant Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA/NV topping the list at a value of $11.3 billion USD. 40% of the top ten outbound deals were made with European companies.

As for inbound transactions, only one of the highest ranking deals was made by a European company (Sandoz International GmbH’s acquisition of Aspen Japan KK at a value of $441 million USD), with the key companies being Japan’s Softbank and South Korea’s NAVER Corporation who increased their existing 73% stake in LINE Corporation to a complete acquisition at a value of $3.4 billion USD in December 2019.

This week, we were fortunate to have the chance to speak with Akio Fujii, a longstanding specialist in working on Japan M&A, both between Japanese companies as well as between Japanese and global companies. He kindly agreed to give us the low-down on his key professional endeavours, experiences in the M&A world, and some advice for foreign businesses looking to do deals in Japan.

Check out his latest article over on LinkedIn entitled ‘What it Takes to Change Japan’.

I see that your background was initially in corporate banking, how did you get into working with Japan M&As?

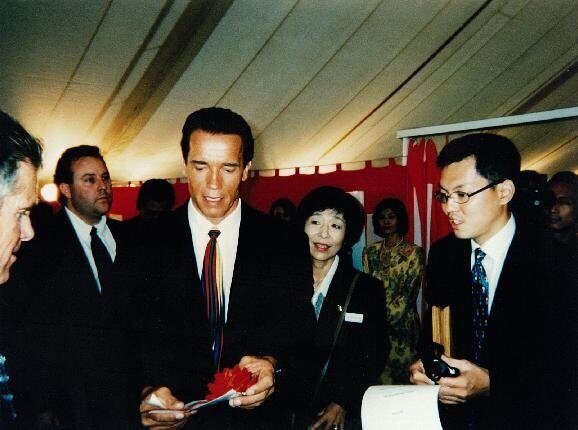

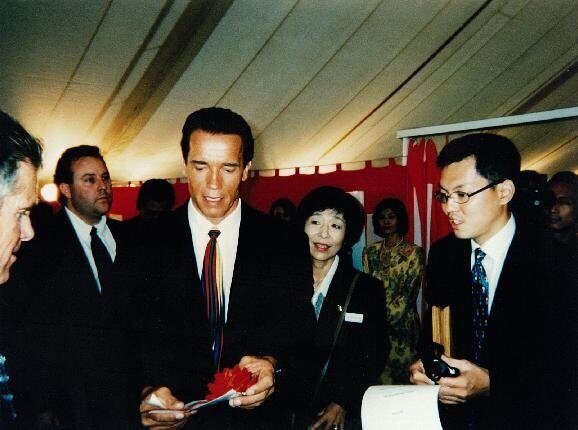

Akio: “Back in the 90s, many Japanese financial institutions did not divide corporate and investment banking functions into separate entities. While engaging myself in marketing activities at the opening of Universal Studios Japan (USJ), as a secondment from the bank, I was also indirectly involved in executing the financials of the project. My boss at the bank, a part-time Corporate Auditor for USJ, was the General Manager of the Business Development department, which was also responsible for M&A advisory services. After more than two years working at USJ, he invited me over to the exciting world of M&As.”

What’s your experience with cross-border M&As?

Akio: “I’ve closed many cross-border deals, but my very first project was highly memorable in many ways. It was certainly a good application exercise as the deal involved a delicate use of the knowledge I’d gained in practice. A German public company acquired a group of Japanese entities owned by an individual. The consolidated B/S (Balance Sheet) was in an insolvent state. The targeted company manufactured and distributed a series of well-recognized consumer goods. The primary entity was equipped with a few patents which strongly protected its core manufacturing technologies for the future.

The buyer wanted the R&D function, factories, supply chain, client accounts as well as the brands, but most importantly, they wanted to acquire the patents and recognize the continued employment of an inventor directly involved with the existing intellectual properties. The seller guaranteed his company’s loan repayment to my bank, and his shares in the business were the only significant asset left. So, we had to set up a Chinese Wall between ourselves and the corporate banking team in order to prevent the potential conflict of interest. We, representing the seller side, accommodated the due diligence process and advised the simultaneous Share Transfer and Employment Agreement negotiations. I’ve had a lot of success stories over the years, but the tombstone commemorating the closure of this deal is still displayed in my den today.”

Tell us about working on cross-border PMI (Post-Merger Integrations)

Akio: “Cross-border PMI projects are often challenging. The M&A process is pretty straightforward thus the fiduciary duty of responsible board members is crystal clear. But, PMI is a corporate blending process which involves qualitative issues including cultural differences. There is no “manual” for this process and each project is uniquely different. This is notably the case with Out-In M&A PMIs where a foreign party buys a Japanese company. The new parent company is in a stronger negotiating position, so they tend to demand that the new subsidiary adjusts itself accordingly, not the other way around, or else an exception will become a precedent.

I was involved in an acquisition deal which involved billions of dollars. The project consisted of an acquisition of a worldwide business scattered across 35+ countries. The US buyer had prioritised contractual efficiency and cost effectiveness and in doing so they subordinated local customer satisfaction, a crucial aspect for the Japanese subsidiary where the customers are seeking quality.

One small mistake in judgement can jeopardize the top line of your P/L (Profit & Loss statement). For example, one global logistics agreement which would take care of all supply chain deliveries for 35+ countries is ideal only if the subcontracting vendor can be designated by the local subsidiary. The new parent company did not like this approach as it was out of their scope and would inevitably increase SG&A (Selling, General & Administrative expenses). If you are an external consultant (i.e. not a principal employee of the buyer remotely managing the PMI process from outside Japan) they can accuse you of displaying favoritism toward a particular vendor. Sometimes, the Japanese “Nominication” culture of wining & dining can mislead the buyer so you have to be very careful. At the end of the day, we were able to incorporate the designated subcontractor, but it certainly left behind an unpleasant aftertaste.”

And how about cross-border turnarounds?

Akio: “I was involved in helping turn around a chronically deficit entity, a US subsidiary of a Japanese public company. It was in a typical metabolic condition, and while the total revenue was significant in size, its operations were not profitable. It was a coin-operated amusements company consisting of both manned and unmanned locations throughout the US. It was the time when two consoles, PlayStation3 and XBOX 360, were taking the consumer gaming market by storm so customers were less attracted by arcade-style video games.

For the company, we had to simultaneously change the amusement machine portfolio from video games to crane prize games, sell used video games by hosting nationwide auction caravan, harvest used parts and circuit boards for resale, shut down unprofitable locations and negotiate penalty fees with the landlords for early retreats. This also included the layoff of employees and negotiation of severance packages among other undesirable activities.

We also implemented business development to increase the number of accounts thus locations. Manned facilities emphasised redemption games like the type you’d see at Dave & Buster’s and Chuck E. Cheese. We also supplied gorgeous prizes featuring Dragonball Z and Naruto characters, a series of products manufactured by our sister company in Tokyo. We collaborated with a Japanese pachinko manufacturer and an American ticket redemption game manufacturer to convert a Japanese pachinko machine into a redemption game and set up a location test in Las Vegas, since Nevada has the most relaxed gambling laws in the US.

These unique attempts made the local employees feel that they were part of a Japanese entertainment conglomerate. At the end of the day, we had to establish a feasible chained network where manned facilities were profitable on a standalone basis and where unmanned facilities were efficiently located for the route managers to frequently visit. Prior to this turnaround, all field managers rotated the game machines spontaneously in order to maintain successful substitution. To do this conveniently, there were a dozen warehouses throughout the nation. We reduced this to just three warehouses strictly designated for repairs as, unlike video games, crane machines were all about prizes and required less maintenance.

We also educated field employees through regional training programs to become more responsible toward profits rather than revenues. As a result, they became aware of fixed asset book values, their life expectancy and straight-line depreciation, something they had never heard of before. They also acquired the skills to manage prize inventories. It was all about educating the employees to proactively participate in managing the company, recognize mutual objectives and award those who accomplished their goals by applying incentive bonuses. Now, they are able to reverse calculate their revenue goals for the areas they are responsible for. I trust my former colleagues agree with me, but we worked like hell!

Still, the efforts and outcomes were visible and the associated fatigue was somewhat comfortable. Having a sense of accomplishment is so very important. The whole process was filled with issues. As the President & CEO of the company, I even received threatening phone calls from those I had to layoff and, as a result, I suffered with a stomach ulcer for a few days. The business unit head office and the holdings company in Tokyo wanted to micromanage the process while the regional holdings company also demanded periodical reports as we were negotiating asset impairments and tax benefits with our accounting auditor.

A lot of people wanted to involve themselves and grab a piece of the action. In the Japanese business world, the metaphor heso ga mienai is sometimes used. It means, “We can’t see the belly button (point of compromise)”. I would regretfully have to say that we winded up in that state many times, but together with the local managers, we co-developed a hybrid cultural environment where local employees were comfortable with taking creative approaches and the risks associated with doing so.”

What kind of environment are Japan companies having to work with right now?

Akio: “The Japanese economy has been experiencing stagnation for three decades now. The average EV/EBITDA* multiple of the Tokyo Stock Exchange is far lower than that of the New York Stock Exchange and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. Economic measures of Abenomics have limitations and investors are not attracted to inward-looking companies when the population is declining and the labour shortage is becoming more visible. And so the domestic market is starting to shrink. This means that many Japanese companies inevitably have to go global, but scaling their successful business outside the country isn’t that easy.

Abenomics, together with the Bank of Japan is maintaining an ultra-low interest rate policy for the Japanese yen. Therefore, companies with an ample amount of cash will have to execute either greenfield investments, In-Out M&As or both otherwise they will have to make a precedent of increasing dividends. With a cross-border M&A, a company would typically hire an investment bank, execute due diligence and obtain a valuation report before receiving authorisation from the board to acquire a foreign company. Upon meeting the consensus, the board director in charge will explain the estimated IRR** or the business plan on which the valuation was based.

However, 2-3 years later, we are hearing numerous suggestions from the accounting auditors to recognize impairment losses because actual performances during the post-M&A period are far from the initial projections, so the auditors would want to carve out a partial or full balance of goodwill. Since this is an objective assessment of the result, the active shareholders are now demanding to incorporate a clawback provision on the Articles of Incorporation, so that the board director in charge will have to refund his/her incentive bonus received upon the closure.

A story like this is repeating itself in Nikkei Newspaper constantly—it’s like deja vu. Japanese companies have applied Western style capitalism, but they have neglected to foster human resources capable of managing global business operations. When they see Nissan’s recent experience with Carlos Ghosn, some Japanese companies may feel it’s too risky to hire a foreign nationalised Board Director.”

* EV/EBITDA multiple is one of the iconic KPIs for measuring the attractiveness of a public company. It simply tells you how many years it takes for a 100% buyer of the company to recoup its investment.

** IRR stands for ‘Internal Rate of Return’.

Are there any short-term solutions to the issues faced by Japan?

Akio: “I don’t think there is a shortcut to resolving the state of current Japanese companies. Where we are today is a result of miscellaneous negligence cumulated over the years.

For example, Japanese CxOs have continuously expressed their resistance to change in terms of company organization and function. Roles & responsibilities including the handling of products and services, and the cultivation of sales are strictly determined and creative ideas evolving from the present state were often seen as taboo since, from a cultural standpoint, the incremental hassles were not welcomed. The organizations functioned with vertical lines of reporting and cross-functional efforts were subordinated.

Japan was once called the most technologically advanced nation in the world with its quality electronic appliances. However, ever since the introduction of the iPhone, Apple has increasingly dominated the audio, PC, TV, video deck, GPS navigation, and game console functions. Smart devices have changed the lifestyles of billions of people around the world while industries in Japan eroded. This unfortunate tendency was generated from Japanese being so used to focusing on what’s in front of them that they didn’t care about viewing business horizontally with a sense of radical open-mindedness. It’s as if they’d been educated to compete like race horses wearing blinkers.

Another example is English education in Japan. For nearly five decades, there has been an emphasis on English writing—primarily grammar structure, vocabulary and translation—but not enough focus on reading, speaking and debating. One of the defining national characteristics of the Japanese is harmony and avoidance of unnecessary conflict. Many say that discussions and debates should be avoided while they demand to “read the air”. The American standard is not the global standard and English is certainly not the only language in the world. Nevertheless, being able to communicate in a language other than Japanese creates a whole new market for them and revolutionizing the education system would certainly help to develop the required skill set.

The Japanese are generally reticent and equipped with a huge sense of perseverance. If the change of direction is set and a consensus is met, I’m sure the mentality will change, but it will take sometime to recognize such a trend.”

Where does Japan sit on a global scale when it comes to M&As? Do you see it as being more, or less, competitive?

Akio: “M&As are a quick and easy method of substituting a greenfield investment. It’s a symbolic corporate event which the market has accepted in recent decades despite the fact that there are still some CEOs who are opposed to the idea because they know how difficult it is to blend corporate cultures. Nevertheless, I think we can say that Japan is certainly one of the key players in the global market.

RECOF announced that there were 4,088 M&A deals in 2019, which is at an all-time high, marking a 6.2% increase from the previous year. Many mature companies and buyout funds acquired Fintech related startups which totaled 1,375 deals, approximately 30% of the whole. In-out M&As totaled 826 with 303 of these in Asia, 258 in the Americas and 195 in the EU. In-in M&As totaled 3,000, of which 999 were investment exits of startups. Out-in M&As totaled 262 with 133 buyers from the Americas, 94 from Asia and 30 from the EU.

Based on these figures, and considering the upcoming shrink in the market, Japanese are yet to be aggressive about going global. They are well-aware how challenging it is to adapt the domestic business model for an overseas market in order to scale the business. So, M&As are certainly a preferred method since there’s no need to start from scratch. When a company is on sale outside Japan, they also know that in many cases, Japanese are asked to take the opportunities at a higher price—paying a premium to ensure favourable auction results. Therefore, I believe there is still a lot of breathing space for Japanese to become more competitive and this is something that they will need to polish through further trial and error.”

What advice would you give European companies looking to make a deal with a Japanese company?

Akio: “I would definitely recommend weighing the emphasis on PMI (post-merger integration), while due diligence and negotiations are taking place. In many cases, whether an In-out or Out-in M&A, Japanese companies appoint their Corporate Planning Department staff to facilitate the project management. They would negotiate with the seller or buyer to determine the deal structure and the price. The valuation range is usually determined by the buyer’s financial advisor, an investment bank. So, the process is in fact pretty straight forward.

Once the deal is closed, operations are handed over to the Business Department who often start PMI considerations from scratch. This is the main reason why most M&As are considered to be failures in Japan. During the pre-M&A phase, the seller of shares is the negotiating party, so the potential counterpart for PMI is usually out of the loop. But, it’s vital that the buyer involves these people as a prerequisite or the chances of failing will increase. I would personally weigh 90-95% of my negotiating time on PMI so that a seamless transition can be realized right after the closure of the deal.”

In your experience, how long do Japan M&A negotiations typically take, compared with other regions?

Akio: “This is a tough question as it differs case by case. But as a benchmarking period, I would set 6 months. When I took on a project management role for the merger of Bandai and Namco, the negotiation process took 5 months, but the transaction to actually integrate the businesses took 9 months. It was a case of two public companies forming a mutual holdings company and we had to undergo numerous administration procedures that would not be required for private companies.”

Is there a particular industry seeing the most M&A Japan deals being made?

Akio: “To be specific, I would say SoftBank Group is the most aggressive player in the marketplace. They have a CVC function called Vision Fund so it’s not exactly M&A, but they are certainly one of the major Japan M&A players. Pharmaceutical and beverage companies are also very active in this space.

There is a Japanese phrase, suji ga yoi which can be translated as “to have an aptitude”. Japanese companies are very nervous about off-the-book and contingent liabilities especially in the case of cross-border deals. So, many Japanese public companies search for deals deriving from antitrust considerations. In 2016, NTT Data acquired DELL’s cloud storage services in the US as a result of Dell’s purchase of EMC. Asahi Holdings acquired companies in Italy and Netherlands as a result of Anheuser-Busch InBev buying SABMiller. In 2018, Taiyo Nissan acquired multiple businesses in 12 EU countries owned by US-based Praxair subsequent to their merger with Linde. These are all public companies which applied a sufficient level of corporate governance. Deals like these make a perfect fit for prudent Japanese executives.

In Japan, mature public companies outsource the support of mid-term business plan developments to consulting firms like BCG and McKinsey. M&A advisory services are consigned to investment banks, accounting firms and law firms. PMI activities are outsourced to the Big Four and Accenture. Turnaround advisory services involving layoffs are outsourced to outplacement firms like Mercer and Challenger, Grey & Christmas. These firms are all battle-hardened veterans who are well aware of the risks involved.”

So what’s next in the pipeline for you?

Akio: “Right now, I’m visiting many Japanese companies to grasp their needs and sell my services as part of my business development activities. That said, I’m open to taking on regular, ongoing employment with a global consulting firm or global private equity fund should the opportunity arise.

Essentially, I’m a self-employed management consultant, promoting myself as a PMO (Project Management Office) Lead. If a Japanese public company wants to consign me, I will work on a fixed monthly pay basis so there will be no retainer nor success fee involved. My team members are usually chosen from the company with supplementation from their law firm and tax accountants. I work on a project-to-project basis so there is no pipeline. For example, if a Japanese company invites me to turn around their subsidiary in the US, I will ask for a working visa and then work on-site. You can think of me as a hermit crab renting a house from one place to another.

With the growing awareness around compliance, there is definitely a tendency for consultants to keep clients at arm’s length, which means that companies are becoming thirsty for strategic yet hands-on executions. Their clients know that the consulting firms’ disclaimers will basically protect them from possible indemnifications. My policy is to co-work with employees head-to-head, accept creative ideas, come to a consensus and execute the plan together so the process itself becomes on-the-job-training. Needless to say, this approach will save the company millions of dollars while intelligence is collectively accumulated in-house.”

Tokyoesque would like to thank Akio for his time in answering our questions. Please get in touch if you require any assistance with developing your presence in the Japanese market, whether that’s related to M&As, building partnerships, localisation of content, cultural insights and much more.